It was a banner night for New York’s second baseball team. I didn’t want it to end. Pete Alonso’s getting a statue on Queens Boulevard and they’ll be picking shards of Jesse Winker’s shattered helmet out of the dirt in Milwaukee for the rest of time. I’m still buzzing. This is one of those rare moments where writing doesn’t feel like torture, but my boss will only let me publish this if I make it about advertising somehow, so we’ll figure that out together in real time. But for now: read on if you’re into the magic of baseball. (And if you’re not I cannot in good faith advise that you proceed.)

First off, I feel duty-bound to mention that I am not a Mets fan––

that is, I do not live and die with their wins and losses or follow their personnel moves closely (I was once upon a time such a fan of the Boston Red Sox, but that is for another rant). However! I am a huge fan of what the Mets are, what they represent, and how watching one of their crazy comebacks like the one that happened last night makes me feel.

Oh! Know what? That’s what brand is! The symbol that stands in emotionally for the greater entity! We did it already!

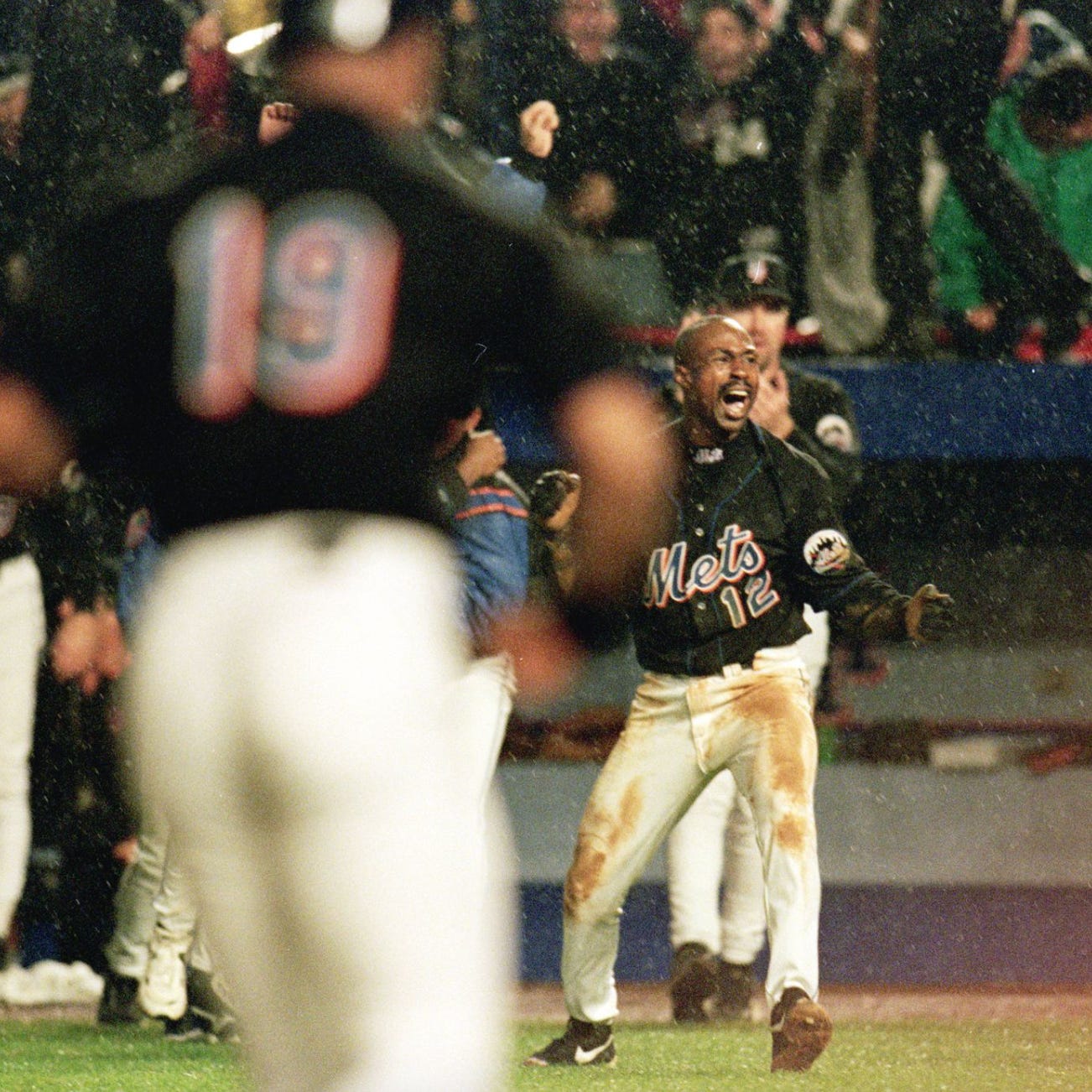

Okay, so: one of my strongest memories from childhood is of watching Game 5 of the 1999 National League Championship Series. That game was played almost exactly 25 years ago, and although I didn’t know it at the time, it encapsulated pretty much everything about what we’ll henceforth call the Flushing Experience.

In a nutshell: the Mets have a unique capacity to fill their entire fanbase with hope, then in almost a single instant to drain that hope, inducing catatonic despair, and then recover and win by way of a statistically improbable sequence. If you had to graph it, it would look something like Kurt Vonnegut’s Man in the Hole story shape. And by the way, I know other teams have had crazy comebacks too, but nobody seems to do it as consistently as the Mets, and I would contend that nobody makes it feel the way they do.

In 1999, it looked like this: in driving rain that on almost any other occasion would have warranted a delay, the Mets played their chief rival Atlanta Braves to a nearly 6 hour stalemate, with the score remaining 2-2 from the 4th inning all the way to the 15th. (For those uninitiated with baseball, though I can’t imagine why such a person would still be reading, a normal game lasts 9 innings.)

In the top of that 15th, the Mets fell behind when extremely average infielder Keith Lockhart hit, of all things, a triple off of Octavio Dotel, driving home fellow extremely average infielder Walt Weiss, silencing the Shea Stadium faithful, and seeming to condemn the Mets to a soul-crushing, season-ending loss on their home field.

Now, it’s important to note a couple of things here. One is that triples are weird. They’re kind of like the Mets comeback of hits. In order for them to happen you usually need a fast player, a ball hit into an outfield gap, and a weird bounce. As of this writing, triples represent less than 1% of all hits in the history of baseball.

The second thing worth noting: none of those elements were present for Keith Lockhart’s triple. Keith Lockhart was, I don’t know, kinda fast when he tried? And the ball he hit was a somewhat well-struck line drive toward the gap in right center field, but he didn’t get enough of it to reach the wall, and if the guy playing center field had gotten a slightly better jump it would have been a simple flyout, and Walt Weiss would have remained at second base.

But that’s not what happened. What happened was: Shawon Dunston, a New York City native, former number one overall draft pick, 2x All Star, and by this time journeyman veteran clinging to the last semblance of an underwhelming big league career, saw the ball late, couldn’t get there in time, and let it land right at his feet, where it skipped past him on the very wet grass, all the way to the outfield wall, where his much younger and more athletic teammate Melvin Mora fielded it just in time to prevent an inside-the-park home run.

Okay that was a lot––I promise we’re getting somewhere

So that brings us to the bottom of the 15th inning. Last chance for the Mets. And who do you suppose is the first player to bat? Why, it’s center fielder and soon-to-be-unfairly-disgraced-in-the-New-York-press Shawon Dunston. He’s the eighth batter in the order (again, this is out of 9 (yeah, baseball’s got a thing with the number 9)), meaning not much is expected of him, and at this point he’s 0-for-2 with a strikeout. The rain is falling harder, the fans are out of it, and the Braves are starting to think about their imminent World Series matchup with the other New York team, the Yankees, who are 3-1 up on the Red Sox in their league championship series. At this point everyone’s just hoping the killing will be swift.

And then…something strange, something inexplicable, something storylike happens.

Shawon Dunston gets on base. And he does it in the most Mets way possible.

In that driving rain, against a fresh-armed pitcher 14 years his junior, after working the count to 3-2 (I’m done explaining baseball stuff now), he fouls off not one, not two, not three, but six consecutive pitches. Six!

Okay, one more baseball explanation: pitchers hate foul balls. They might hate them even more than they hate home runs. The reason for this is that foul balls almost always mean that a pitcher did his job well, meaning: he got a pitch in the strike zone, but not somewhere that a batter could do anything productive with it. But when a hitter manages to foul such a pitch out of play, as opposed to hitting a weak ground ball, popup, or missing it entirely, the at-bat turns ever so slightly in his favor. The hitter has avoided an out, gathered data by seeing another pitch, and prolonged the moment of tension and opportunity, whereas the pitcher has tired himself slightly, been frustrated by the foiling of his best effort, and now has to strategize about his next pitch knowing that the hitter knows more about his arsenal.

And, in the case of Shawon Dunston, the hitter also got the crowd back into it.

After nine whole minutes, on the 12th pitch of the at bat, with the Shea crowd newly buzzing with a sense of possibility, Shawon Dunston poked a ground ball through the middle of the infield for a single. Bob Costas, broadcasting the game for NBC, appropriately deemed it a “tremendous at bat,” and what followed, though it was still statistically unlikely, felt inevitable. Dunston stole second base, then scored to tie the game, fully redeeming his earlier mistake, and then, with the bases loaded, Robin Ventura hit the only thing weirder than a triple, his now-iconic grand slam single, where after sending an absolute missile over the wall in right field he was mobbed by teammates before he could finish rounding the bases.

Baseball fan or not - I’m grateful if you’re still with me

Last night looked like this: In the bottom of the 7th inning, after the Milwaukee Brewers broke a 0-0 tie with back-to-back solo home runs, sending their crowd into a frenzy, and with the Mets desperate to just get out of the inning, William Contreras hit a high popup to the first base side. There were two outs, the ball was by any metric extremely playable, and Pete Alonso, in the final year of his contract, in what was looking very much like the final game of that final year, began chiseling his name into the womp womp section of Mets lore by very awkwardly misplaying it, rendering what should have been the final out into what was effectively one of those foul balls pitchers hate so much, and allowing the inning to continue.

Lucky for him, the Brewers did no further damage, and two innings later, in the top of the 9th, his MVP candidate teammate Francisco Lindor had his own mini version of the Dunston at bat, working the count until he was walked, and was then advanced to third on a Brandon Nimmo singled up the middle. Two men on, one out, Alonso up.

I simply cannot provide a satisfactory or sufficient explanation of this to the uninitiated, but to anyone who has spent time watching the Mets, it was very obvious what was about to happen.

Sports aren’t scripted, but the Mets have a brand, the aforementioned Flushing Experience, and that brand has a mascot, a role filled by different players at different times for different reasons. Let’s call it the Redeemed Man. In 1999, that man was Shawon Dunston, and last night, we all knew before it even happened, it was Pete Alonso.

I’m not gonna try to write this up. Watch it here.

One more advertising beat so Kingsland lets me keep writing these:

If you’re still reading, I imagine you know it’s been almost 40 years since the Mets won the World Series. In other words, Shawon Dunston’s turn as the Redeemed Man in 1999 did not spark a playoff run culminating in the ultimate glory. In fact, the Mets lost that series two nights later, and they probably won’t win it this year. But who ever gave that Braves team another thought? Or the Yankees team that swept those Braves one round later? (Okay, fine, lots of people probably. Yankee fans can’t get enough of their own success.)

Moments like 1999 and last night that are just that: moments, and you might think of them in the same terms you think of driving a new car for the first time, or cracking open a can of Coke, or arriving in a place you’ve never been before for vacation. The experience matters because of what you imbue it with beforehand, and then almost never lives up to the wild expectations you carry in your heart. The new car becomes your car. The first Coca-Cola you drink tastes like nothing you’ve had before, and you chase that sensation forever. Halfway through your vacation, you start thinking about home.

In other words, products don’t have to deliver. But brands do. And the Flushing Experience always will.