{Gatekeeping}

“It seems like there are always gatekeepers. People between you and the people who are moved by your work. They often make a beautiful thing creepy.” - John Lurie

Where have all the experts gone? So goes a constant refrain in modern American culture. In advertising we’re constantly citing that brands are more trusted by consumers than the government, doctors or the media. It’s unclear, however, if anyone agrees on whether or not this is a good thing. Sure, the experts have done us dirty in the past…but so have plenty of non-experts. With less expertise there’s more fraud, a less-educated general public and an environment that’s ripe for conspiracy.

When we talk about this, we’re really talking about who gets to control the information we receive everyday, and whether or not anyone actually should. The gatekeepers are dead. Long live the gatekeepers.

Connections:

🪐 Bodhisattva / Heimdall / Janus - A recurrent figure across faiths, these are liminal deity gatekeepers that protect the doorway to enlightenment, and usher recently deceased people into the next world.

🏀 Dikembe Mutombo / Roy Hibbert / Shawn Bradley - Modern basketball strategy is so dependent on the three point shot that there’s not really a place for the rim protectors of decades past. Until about ten years ago you could count on just about every team employing at least one seven-footer to gatekeep the paint, however.

👾 Dungeon Master / Referee / Arbiter - Why do we love games? Because unlike life, games have rules, and rules control the fun. These gatekeepers enforce the rules. Or, if you believe in various NFL conspiracy theories, the script.

⭐ Stonehenge / Mona Lisa / The Great Wall of China - Nobody would contest that in a vacuum these historical sites are worth visiting, but they’ve all been ruined, and in some cases physically damaged, by too many people going to see them. Could’ve used more gatekeeping.

🎥 David Lynch / Marina Abramovic / Gabrielle Lutz (née Gary) - If you don’t like Lynch’s movies, Abramovic’s exhibits, or Lutz’s books, a fan would say you probably just don’t get it, and they’d really enjoy telling you that.

👀 Mrs. Robinson / Nurse Ratched / Sauron - Fictional gatekeepers hell-bent on ruining our heroes’ lives.

🔧Apple / Tesla / John Deere - Three major consumer brands that have embraced gatekeeping as product strategy, making it impossible for consumers to perform alterations or repairs on their products, and in turn to fully own the goods they have purchased. For their part, Apple has recently begun public supporting right-to-repair legislation, but only time will tell.

The Commonplace: Gatekept

A commonplace book is a hodgepodge of secret knowledge, new ideas, old quotations, and odd observations compiled for future reference and reflection.

Sumo –– The Freakonomics team claims that sumo wrestlers essentially function as their own gatekeepers when it comes to leveling up as a professional. In a nutshell, on the occasions when a wrestler who has already secured his advancement faces a wrestler who needs one more victory to do so, the latter wins a disproportionate amount of the time.

Do We Actually Need More Gatekeeping? - Comedian Brian Park thinks so, in his “take” with Kareem Rahma’s popular @SubwayTakes channel.

I Got Ye –– Australian musician Gotye has famously never taken YouTube ad revenue for his 2011 megahit “Somebody That I Used to Know,” (yes that song is now old enough to be Bar Mitzvahed) nor has he ever charged others for sampling it. A non-gatekeeping king.

The New Gatekeepers - The Cut’s Ann Friedman analyzes how the internet brought about a new generation of gatekeepers, and how the more things change the more they stay the same.

Picture This: Rick Owens on Reddit - Fashionistas love to gatekeep. Here’s an entertaining Reddit thread discussing whether or not Rick has been gatekept enough.

Who Gatekeeps the Gatekeeper?

-Douglas Brundage, Founder @ Kingsland

A gatekeeper, traditionally, is a fairly self-explanatory role. A job at least as old as civilization, every single belief system involves a kind of steward to the afterlife (Cerberus, Saint Peter, Anubis, etc.), gatekeepers were a symptom of urban planning. As cities, towns and military fortifications evolved, someone needed to keep watch for bandits, wolves and Trojan Horses. Hence the gatekeeper - a lowly job that, over time, became imbued with much power. In fact, the trend of giving influential people the “Key to the City” dates back to these times, as being able to physically come and go as you please was a privilege rooted in gaining the trust and loyalty of the city’s leadership.

Today, gatekeeping is considered more of a mass communications theory than an actual job description, although gates around the world do still require keeping. Gatekeeping, simply put, is the controlled flow of information and services by supposed “experts.” The term was coined as a media theory in 1942 by German-American academic Kurt Lewin, known as one of the modern pioneers of social, organizational, and applied psychology. A gatekeeper, whether the Church in the Middle Ages or the news media in later years, does the following:

Surveillance/Intelligence Gathering - A gatekeeper gets information earlier than the rest of the population. This used to require “boots on the ground,” especially in journalism, but nowadays can involve intense online research as well as human sources.

Edit/Determine “Newsworthiness” - Here’s the part where the gate gets kept. These individuals or committees then decide what they deem important enough for people to know. This may involve a rigorous expert examination of the data, but more recently it also could align with an ideological imperative held by the gatekeeping organization. If something could be damaging to their “cause,” they can simply choose to omit it, even if the information is important and true.

Dissemination - A gatekeeper, by definition, needs some kind of population they are sharing information with. This could be adherents to a religion, subscribers to a publication, viewers of a piece of content, or, of course, social media followers.

However, especially in the 21st Century, gatekeeping has extended beyond the traditional media format, seeping into almost every element of our lives. Examples abound in contemporary American culture, including but not limited to:

Credentialism - The Western world, in particular, has been obsessed with credentialing for at least the last century. The idea is that people should have to pass some kind of trial to demonstrate their expertise in a subject, and that their views should only become valid when a committee of like-minded experts agree that this individual deserves recognition, usually in the form of some kind of title and/or certification (Doctor, Esquire, Tenured Professor, Fork Lift Certified, etc.). The roots of this practice are both well-meaning and nefarious, as credentialism certainly has cut down on the number of fraudulent services being offered on the market, but was also historically used to eliminate unwanted groups - women, Jews, BIPOC Americans, LGBTQ+, and anyone else who didn't meet the imagined standards of certain professional spheres. In fact, my own family had to change our last name from a distinctly Jewish one to Brundage in order for a Great-Uncle to get accepted into an Ivy League Medical School.

Peer Review - An academic practice that’s less nefarious than Credentialism, Peer Review is still a prominent form of gatekeeping. The concept is that even credentialed experts should not be allowed to publish academic research until that work has been reviewed and approved by similar experts in their field. In practice, peer review is largely harmless and positive, but it too can fall victim to groupthink. New ideas or findings that go against a perceived norm often struggle to make it through peer review, especially nowadays, and at the same time when a dubious claim (like the now-debunked idea that women face a “fertility cliff” at age 35) does make it through peer review, it’s considered more legitimate than before.

Doublespeak - The way we talk in corporate America is a form of gatekeeping, and it’s no coincidence. In fact, according to “The Firm: The Story of McKinsey and Its Secret Influence on American Business,” management consultants purposefully crafted a lexicon of complex, borderline nonsense terminology in order to confuse and obfuscate information for both their clients and the population at large, making them seem so much smarter in the process. They were inspired by lawyers, who famously speak in Latin ad absurdum. This has unfortunately spread with the popularity of MBAs, who have infiltrated almost every element of corporate society, making communication all the more difficult.

From a marketing perspective, brands also gatekeep, especially in specialized industries. Trade organizations tend to dominate here. Take, for example, the diamond industry’s famous “4 Cs” - Cut, Clarity, Color and Carat (sometimes with “Certification” included as a fifth “C”). Created by the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), these are general guidelines to apply when reviewing a diamond’s value, but most Gemologists agree it’s little more than a marketing ploy. Thread count is a similar construct - a largely made-up gimmick created by Big Sheet to sell you more Egyptian Pima Cotton pillowcases.

So, what do all these gatekeepers have in common? “Quality control” of some kind, with the side-effect of being able to create culture, consumer behavior and community norms. But all that started breaking down around 20 years ago.

Meet the Gate-Crashers

By the dawn of the new millennium, a shift began on several fronts.

Anna Wintour, an elderly British woman who once promised never to talk to Kim Kardashian and then put her on the cover of Vogue, created “Fashion’s Night Out,” which was a complete failure, and heralded the strong future for department stores. She also ran the American fashion industry.

Record Labels rested on the laurels of CD sales and had zero appetite for the digital future that was rearing its head. They sought hitmakers for radio play over artists with new sounds or stories to be told, and executives were apathetic at best about the emerging popularity of Hip-Hop and EDM. Then Apple announced the iPod.

George W. Bush and his cadre of cabinet members blamed an attack from Saudi-backed, Afghanistan-based Al Qaeda on Saddam Hussein in Iraq, launching a war with implications we’re still dealing with today, and enriching VP Dick Cheney’s former employer Halliburton to the tune of billions of dollars in the process. We’re still looking for those WMDs.

The media was another casualty. From an FT review of “The Men Who Killed the News,” a new book on the subject:

The mistrust of journalists is not new; even Thomas Jefferson, who decreed that “liberty depends on the freedom of the press”, went on to call newspapers “polluted vehicle[s]”. But a century of dominance by media moguls such as William Randolph Hearst, using populism to fuel profits and power, argues Beecher, has eroded any sense of ethical responsibility by owners.

The country began to realize that the people in control of our information, trends and media machine maybe, just maybe, didn’t have our best interest at heart. “Indie/Hipster” was the cultural zeitgeist at the time, and a distinctly millennial sense of ironic contrarianism began to emerge. As our generation formulated a perspective, another funny thing happened: the internet.

As social media proliferated, the powers-that-be lost more and more influence over culture, largely due to inaction rooted in confidence in their own gatekeeping prowess. Peer-to-peer sharing became not only the de facto media consumption habit of the time, but also shaped who and what was cool. JJJJound, originally a Tumblr page, was born in this era. So was Odd Future, the promising hip-hop comedy collective featuring Frank Ocean and Tyler, The Creator, among other future stars. Justin Bieber was discovered on YouTube. 13th Witness became one of the first “Instagram Influencers,” quickly signing deals with brands like Nike. Beauty enthusiasts, fashionplates, frustrated mothers and semi-pro bodybuilders started blogs, and later podcasts, and monetized them quickly (many, like Something Navy, Food52 and Groupon, evolved into brands). Corporate America’s gatekeepers had little idea what to do with this new economy, and in fact many resisted the promise of the internet for up to a decade before giving into social media and e-commerce as the new normal.

With this shift in the Zeitgest came a new form of anti-gatekeeping. All of a sudden, regular people were in charge of disseminating valuable information to the masses and, unlike the powers-that-be, they would share it all openly. It’s in this context that “gatekeeping” in the modern parlance was born, defined as an inherently negative act of keeping a valuable secret to oneself for no reason other than not wanting other people to know.

And so the gates got crashed. “Authenticity” became the buzzword of the moment, and brands began to pivot to work with, and further raise the profiles of, this new caste of influencer: seemingly regular people, often with talent and taste, who had become the new gatekeepers yet abhorred gatekeeping. In a culture defined by irony, the emergent powerhouse creative class was breaking every rule of communication as their fanbases grew. This, of course, had to come to a head.

As early as 2014, people were talking about “The Death of Expertise.” As the Kardashians became more influential than Congress and Facebook more powerful than NBC, disturbing trends emerged. The most obvious one was rampant fraud across social media. Fans bought sneakers off of Instagram only to discover they were extremely fake once delivered. The “wellness” industry became larger than the pharmaceutical industry, with none of the regulation, and influencers started hawking all kinds of supplements, pills and powders with dubious claims. NFTs were…you know, a thing.

While all this was happening, a call for the return of gatekeeping began to get louder. Michael Lewis published an entire podcast about Salvator Mundi, the half-billion dollar “Leonardo Da Vinci” painting bought by Mohammed bin Salman which was almost certainly fake. The “experts” at Christie’s could have declared it as such, but then no one would make any money.

The US Government worked with social platforms and the press to begin pushing for new classifications for both lies and half-truths they didn’t like, referring to them as misinformation, malinformation or disinformation. This classic gatekeeping tactic backfired in its complex verbosity, and people became more likely than ever to trust social media over mainstream news or the government itself. Conmen (and women!) came to dominate every year’s Forbes’ 30 Under 30 as well as new entrants to the House of Representatives. As critics and experts increasingly lost their sway on society, the truth itself became a free-for-all.

Maybe we needed gatekeepers after all?

Gatekeeping for Fun and Profit

Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? is a Latin phrase found in the Satires, a work of the Roman poet Juvenal. It may be translated as "Who will guard the guards themselves?" or "Who will watch the watchmen?" This was, indeed, the inspiration for the comic book series of the same name, but it also explains what has happened to gatekeeping culture over the last quarter-century. No one is watching the watchmen.

We’re exiting an era wherein gatekeeping is simply bad. It’s the guy you know who won’t tell you where he got his coat, or the girl who won't tell you the name of the restaurant where she always photographs her dinner. The company that won’t be transparent. The politician who gives only prepared answers. Sure, all these people suck. But is there a way to leave this behind while returning to some kind of standard of expertise?

Without as much gatekeeping, there’s equilibrium, yes- everyone is technically on the same playing field of information these days. But there’s also no texture, no nuance and very little “newness.” In a monoculture ruled by groupthink it becomes impossible to innovate. Essentially, without gatekeepers, there’s less subculture - and subculture is where all the tastemaking begins.

Enter the new gatekeepers - accessible, but often paywalled. In the doublespeak of marketing, the age of influencer seems to be coming to a close, now replaced with “creators.” These people are simply a little more interesting than run-of-the-mill influencers, who often rose to fame based on their taste level, looks, or personality, but not their ability to produce something of value. The new class of creators are different, most armed with a skillset of some kind that customers find useful, interesting or new.

The most popular of these creators don’t just shill products or sell merch, they actually share their opinions and shape “the culture” in the process. Some are more than qualified (or credentialed) to do so, while others are self-taught and driven by curiosity. Without as many Ivy League degrees and years of journalistic practice, many of these people are actually more engaging critics than the ones still left working for major publications. The new gatekeepers are, on the whole, better-equipped and more in-touch than their forefathers. They're not burdened by dogma, while remaining fluent in the democratic parlance of the Internet. In this way, they’re trustworthy, checking a box for the “authenticity” we all crave.

The rise of Substack itself is aligned with the new gatekeeper class - newsletters like Feed Me, BlackBird Spyplane and The Reveal dive into old subjects in new, engaging and entertaining ways, with no lack of opinions laid bare. Alison Roman and Molly Baz are the new Ina Garten, carrying on her tradition of strong perspectives on traditional recipes (mayonnaise in cornbread!). Even in the delicate arena of politics, the most exciting analysis comes from the independent journalism and creator space. Letters From an American, a fairly nerdy blog started by Historian Heather Cox Richardson, is considered one of the most successful paid publications in Substack history with over one million subscribers.

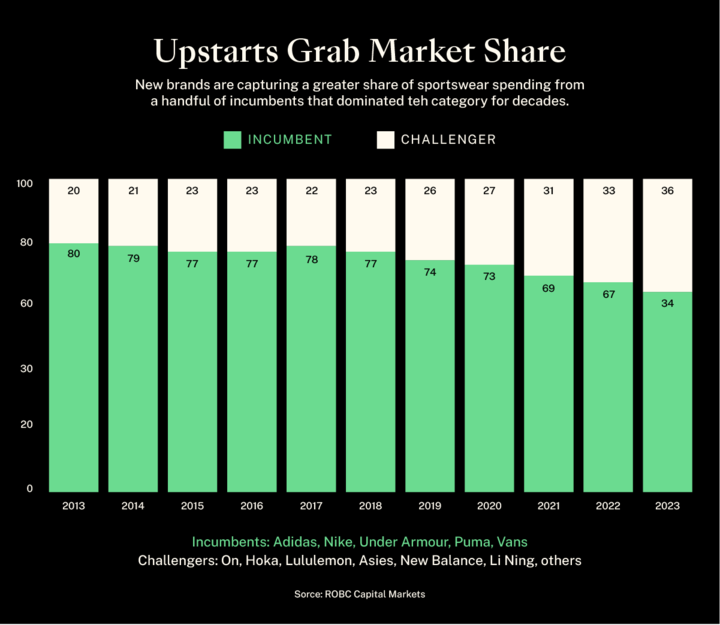

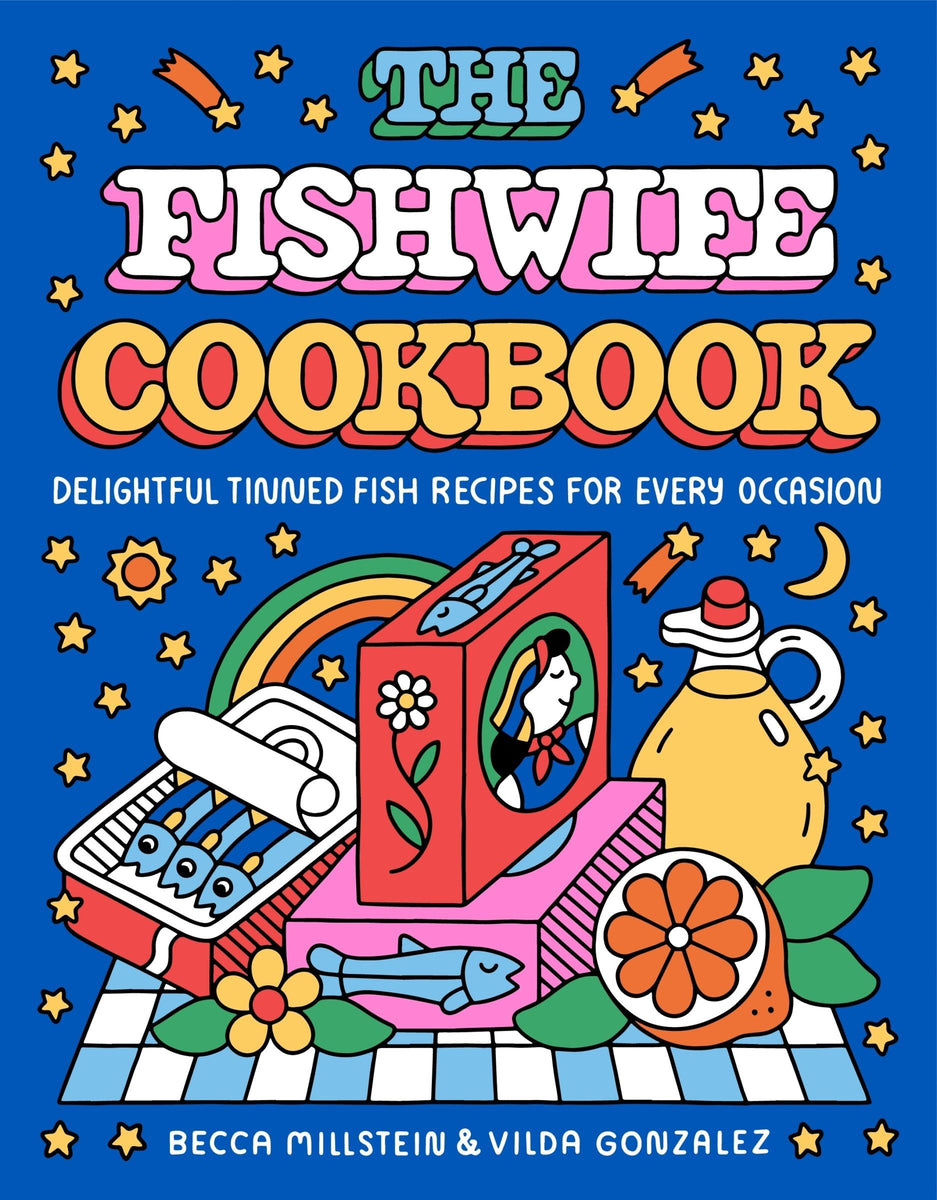

This is already impacting the market on the whole. A new wave of brands like Jacquemus, a reinvigorated Loewe under Jonathan Anderson, HEAVN by Marc Jacobs, Bandit, Telfar, Fenty, ELF, Liquid Death, Black Rifle Coffee, Fishwife, Dude Wipes, Brewdog and more are shaking up business across categories by building unique perspectives, executing unexpected partnerships and always operating with a little bit of mystery. They’re not exactly all gatekeepers themselves, but they’re more than open to working with them.

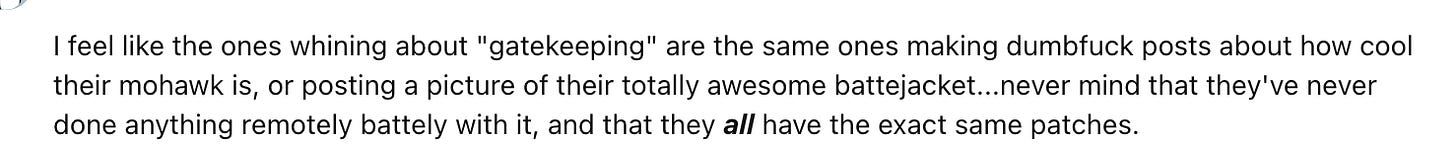

As with any essay worth its salt, we end with a quote from the R/punk reddit community:

No, gatekeeping isn’t very punk. But at the same time, well, it kind of is. When the culture is flat, the phone is the news, and everything new looks old - it’s a perfect moment for perspective. We all have the exact same patches, and that’s boring as hell. It’s okay to think something that’s popular is stupid, or even more importantly something that’s unpopular is cool. This is how culture, and to a broader extent community, gets made. It’s time to prepare for a new class of gatekeepers to enter the scene. The brands that can identify them early and work with them in ways that make sense will continue to win. The brands that don’t might not ever offend anybody, but they also will sink into cultural obscurity. So let’s embrace our new gatekeeping class, keep them sharp and hone their instincts. They’re probably going to shape the future, whether we like it or not.

Moodboard

Reading List:

The Death of Expertise - Tom Nichols was one of the first to sound the alarm on the demise of the 20th century’s gatekeeping class. In the second edition, he follows up on how this rejection of experts has occurred: the openness of the internet, the emergence of a customer satisfaction model in higher education, the transformation of the news industry into a 24-hour entertainment machine, and the (first) election of Donald Trump.

The Algorithm’s Been Hiding Something From You - Is creativity dead now that culture is flat and devoid of gatekeepers? Kirby Ferguson of Everything Is a Remix fame makes his case.

The Leopard - The poignant and spellbinding story of a decadent, dying Sicilian aristocracy threatened by the approaching forces of democracy and revolution during Italy’s unification movement in the 1860s. Gatekeepers no more.

The Firm:The Story of McKinsey and Its Secret Influence on American Business - Management consultants are in many ways the ultimate gatekeepers in corporate America. This book explores how that happened, and what the repercussions might look like.

The Gatekeeper - The “compelling personal story” of arguably the most influential member of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration, Marguerite “Missy” LeHand, FDR’s de facto chief of staff and a consummate gatekeeper.

Contagious: Why Things Catch On - Wharton marketing professor Jonah Berger’s fan-favorite analysis on what goes viral, and why, including lots of juicy case studies like how the spur of anti-drug ads in the 1990s may have actually increased drug use in America.

The Citizen App Remakes Itself - Long considered a crutch for Karens, the local gatekeepers of their communities, to opine on about crime, Citizen is attempting to make their services feel more equitable and less…snitch-y.

Citizenfour – Edward Snowden felt the US government had gatekept enough information from its citizens and, for better or for worse, decided to take things into his own hands in 2013. Laura Poitras’ 2014 film Citizenfour documents this process in real time, and can currently be viewed gate-free on YouTube.

The Shepherd's Life – A sheep farmer’s memoir on his disappearing way of life.

Everybody Who Was Anybody - A biography of Gertrude Stein, one of the literary and art world’s most acclaimed (and acid-tongued) gatekeepers.