{Gimmicks}

“No one ever made a difference by being like everyone else.”

— PT Barnum, from “The Art of Money Getting,” a very strong book title.

A gimmick, by definition, is “a trick or device intended to attract attention, publicity, or business.”

There’s nothing inherently negative in this and, in many ways, it feels synonymous with a description of “marketing,” the circus act we’ve managed to productize, bureaucratize and glamorize into something that seems scientific enough to charge for. Yet today we tend to discredit gimmicks outright. They’re considered cheap, dishonest and too unserious. But… are they really?

This is theme of today’s CODEX, and we hope by the time you’re done reading, you’ll realize the beauty, fun, and market effectiveness that some frivolity can bring to your brand. Let’s get into it.

Connections:

❌ Tesco • British Airways • Doritos - OOH examples from companies that have boldly decided to omit their own logos and brand names. A lot of people are yelling on the internet about these campaigns, which… well, was probably the point.

💯 Ten Thousand Hours • Ten Thousand Steps • Ten Thousand Things — All self-improvement ideas that gained popularity due to their simple numerical rules...indeed, a classic gimmick. Ten thousand hours to be virtuosic and ten thousand steps to be strong have been disproven as useful heuristics over scientific fact, but forgetting the self and being enlightened by ten thousand things still seems like a good idea to us.

📚 Life: A User’s Manual • The Mezzanine • Lightning Rods — Three novels that rely on what critic John Jeremiah Sullivan terms “the deep gimmick”; they all center around a slightly ridiculous conceit, but they work because of their authors’ commitment.

🧛 Dracula • Visible • IKEA — Some more “gimmicky” out-of-home advertising moments that delighted instead of annoyed viewers. No matter how digital advertising becomes, real-world gimmicks always

🐣 Silly Putty • Pet Rock • Tamagotchi — Three toy fads that were pure gimmicks yet captured the minds of culture, and printed money in the process.

🍔 McDonald’s Monopoly • A Free Fighter Jet • A Fake Festival — Three big-money marketing gimmicks gone wrong that resulted in court cases and (very entertaining) subsequent documentaries.

The Commonplace: Gimmick Me This

A commonplace book is a hodgepodge of secret knowledge, new ideas, old quotations, and odd observations compiled for future reference and reflection.

Get Back In The Box – Following a deadly e. Coli outbreak (sound familiar?), Jack In The Box recovered the public’s trust by returning to their original gimmick: their mascot, who was depicted as blowing up the company’s board of directors.

I Hope They Have Seeding Kits In Hell – In 2009, EA Games went full-throttle with the campaign for Dante’s Inferno: sending $200 checks to journalists to “succumb to greed,” hiring actors to protest the game outside of E3, and seeding developers a box that Rickrolled you until you destroyed it with a hammer. Nobody liked it, however DIABLO IV recently took to the streets with a similar stunt that worked well.

Machine’s Gambit — The “Mechanical Turk,” a late 18th Century “robot” marketed as a chess player that could beat any human was really just … a guy dressed up as a robot. As one of the first “artificial” models using human labor, it set the tone for LLMs 2.5 centuries later. Of course by the 1990s, IBM did in fact build a machine that could beat a Grandmaster at chess - Deep Blue, which is also a great Arcade Fire song.

Are Blankets the New Tote Bag? As profiled in Emily Sundberg’s popular “Feed Me” newsletter, brands from Glossier to Ghia to A24 are now making… cozy throws.

Picture This: Building REALLY tiny houses for crustaceans as a marketing stunt. A Japanese real estate company solved a hermit crab housing crisis with custom-designed 3-D printed shells which featured their logo and aesthetic expertise.

Gimme Gimme Gimmick

-Raf Carillo, Creative Strategist @ Kingsland

The word “gimmick” gets thrown around a lot, and when people say it there’s almost always a negative connotation—the tone we tend to use puts it just to the side of “scam.” But why? Sure, snake oil is a gimmick, but so are fun size candy bars, Snapple facts (sorry—“facts”), and the McRib. You’re telling me you really want to live in a world without the McRib?

Here’s a quote from former Duke basketball coach Mike Krzyzewski, substituting the word “gimmick” for “Christian Laettner:”

“You have to think about gimmicks like fire. And you are the superintendent of a building. If you handle them the right way, they can heat up every apartment in the building. But if you don't approach them the right way, they'll burn the building down.”

Coach K is exactly right. When done right, gimmicks can supercharge your brand and make it a permanent part of culture—but they can just as easily stick out like the proverbial sore thumb.

Today we’re going to explore this most mercurial aspect of marketing, from the first instances of the word to modern use cases and why they did and didn’t work.

We’re even going to debut our very own matrix for assessing the effectiveness of gimmicks. And yes, that too is kind of a gimmick.

A Short History

The exact origins are unclear, but the word gimmick is generally agreed to have been coined early in the 20th century. One theory associates it with magicians, whose job is of course to seduce and deceive audiences. Another identifies it as a corruption of the word gimcrack, which refers to a showy object of little or no value. Yet another states that it may have come into use at gaming tables, where it would have referred to “a device for making a fair game crooked.”

It’s fitting that the background of the word for the thing we don’t know how to feel about is itself unclear, because the tendency toward gimmick appears to be innate, inexplicable, inescapable, and deeply human.

In other words, whatever we might think of it, we’re stuck with it, sort of like the need to love, or—more to the point—the need to tell stories. Because gimmicks, when done well, are basically 1.) a compelling narrative, and 2.) an invitation to be a part of something larger than oneself.

So let’s start in a place full of stories, dreams, and community: the department store.

The Universal Gimmick: 99 Cents

Yes, pricing is a gimmick. Price points consistently linger between whole dollar amounts. And odds are that when you purchased the item that’s sitting nearest to you right now (a coffee? A pen?), it was priced with a number ending in 9—probably 99.

Tax and tipping notwithstanding, the 99-cent price point is applied, by some estimates, to over 60% of all products—everything from coffee to candy bars to mobile plans to cars. And the reason is simple: it makes people buy more stuff. (But weirdly, when we get to real estate, the principle appears to flip, with homes listed right at or above the 00 point selling in almost half the time of those listed at 99.)

This gimmick makes us happy and simultaneously induces us to spend, on average, 18% more than we comfortably should. One study at the University of Chicago found that when the price of margarine dropped from 89 cents to 71 cents at a local grocery chain, sales improved 65%, but that when the price fell to 69 cents, sales rose 222%.

This practice, known as charm pricing, began before the word gimmick had even come into common usage. In 1880, Macy’s ran print advertisements touting black silks for sale at several “99” price points.

And yet, the conception of this ridiculously successful gimmick may have been an accident, or rather, the result of a solution to a separate problem. In the late 19th century, if an employee who was routinely tasked with handling cash ever found themselves short on rent, or just feeling a little mischievous, it would have been supremely easy to skim a few dollars from their place of work, and not be found out until much later, if at all.

That all changed in 1879, when a bar owner in Dayton invented and began using the cash register, whose classic “ding” sound made it clear when a sale was being made. The “.99” gimmick forced workers to open the register to make change for customers, thwarting potential theft while making nearly the same amount of cash.

Today, cash is becoming obsolete, and about half of Americans favor getting rid of the penny, but you can bet your bottom dollar that even if that were to happen, the “X.99” price point would persist.

Fire v. Warmth

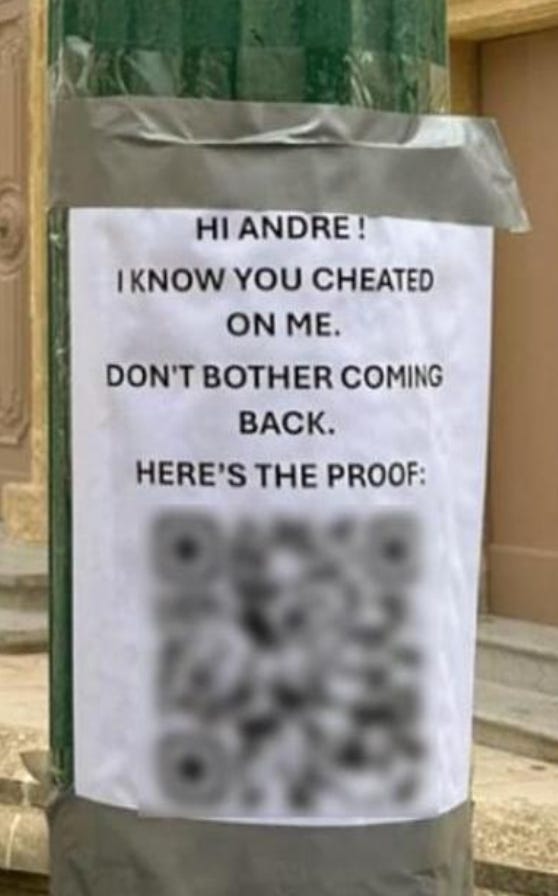

Let’s go back to Coach K’s dichotomy. For the burned-down building, we have the stunt of wild posting a QR code along with an accusation of a total stranger’s infidelity.

This is a gimmick driven by the rubbernecking principle: the concept that no one can look away from a car crash. The accusation catches your eye, you scan the code thinking you’ll see — I don’t know, nudes? — and you’re directed to a company’s product page, an artist on Spotify, or a Substack newsletter. But this gimmick ignores a fundamental reality of the principle, which is that nobody was ever put in the mood to buy or subscribe or become loyal to something after bearing witness to a horrific accident. (Not to mention that QR code baiting has become a favorite practice of actual scammers).

It’s executions like this that make us think gimmicks are bad. The real heart of the problem with these salacious wild postings is that in most cases, the subject matter has little to do with the brand or product being sold — it’s just an exploitation of a low curiosity that may spike short-term traffic, but won’t do much to drive sales or earn trust with consumers. If anything, this gimmick is an ironic and on-the-nose violation of trust, a titillating bait-and-switch. Nobody wants to feel like a sucker or a pervert, and this approach makes you feel like both.

Now let’s look at a nice warm apartment building.

Technically, every US state has a slogan or catchphrase, but none of the other forty-nine seem to matter when you read “Don’t Mess With Texas.”

Originating as part of a campaign to reduce roadside litter (as in “Don’t mess up the way Texas looks”), the slogan quickly became a cultural touchstone, and is now the first phrase that comes to mind when we think of the Lonestar State, despite not even being the official Texas motto. (Know what is, by the way? “Friendship.” Yeah, really.)

Like any gimmick, “Don’t mess with Texas” was conceived to induce a specific behavior from the people who encountered it. It was firmly rooted in a foundational insight, namely Texas’ history as an independent republic—the slogan appealed to Texans’ inherent civic pride and engineered it into action.

The subtext: “Yes, this is the chosen land. Yes, you are lucky to live here. Now act accordingly.” It’s not really about keeping Texas clean; it’s about keeping Texas Texas.

The result? A drastic, virtually overnight drop in roadside litter: 72% between 1987 and 1990. And long-term, a memorable, ownable, repeatable phrase that reinforces an internal sense of community and serves as a warning to all those outsiders who would dare mess.

A gimmick that worked.

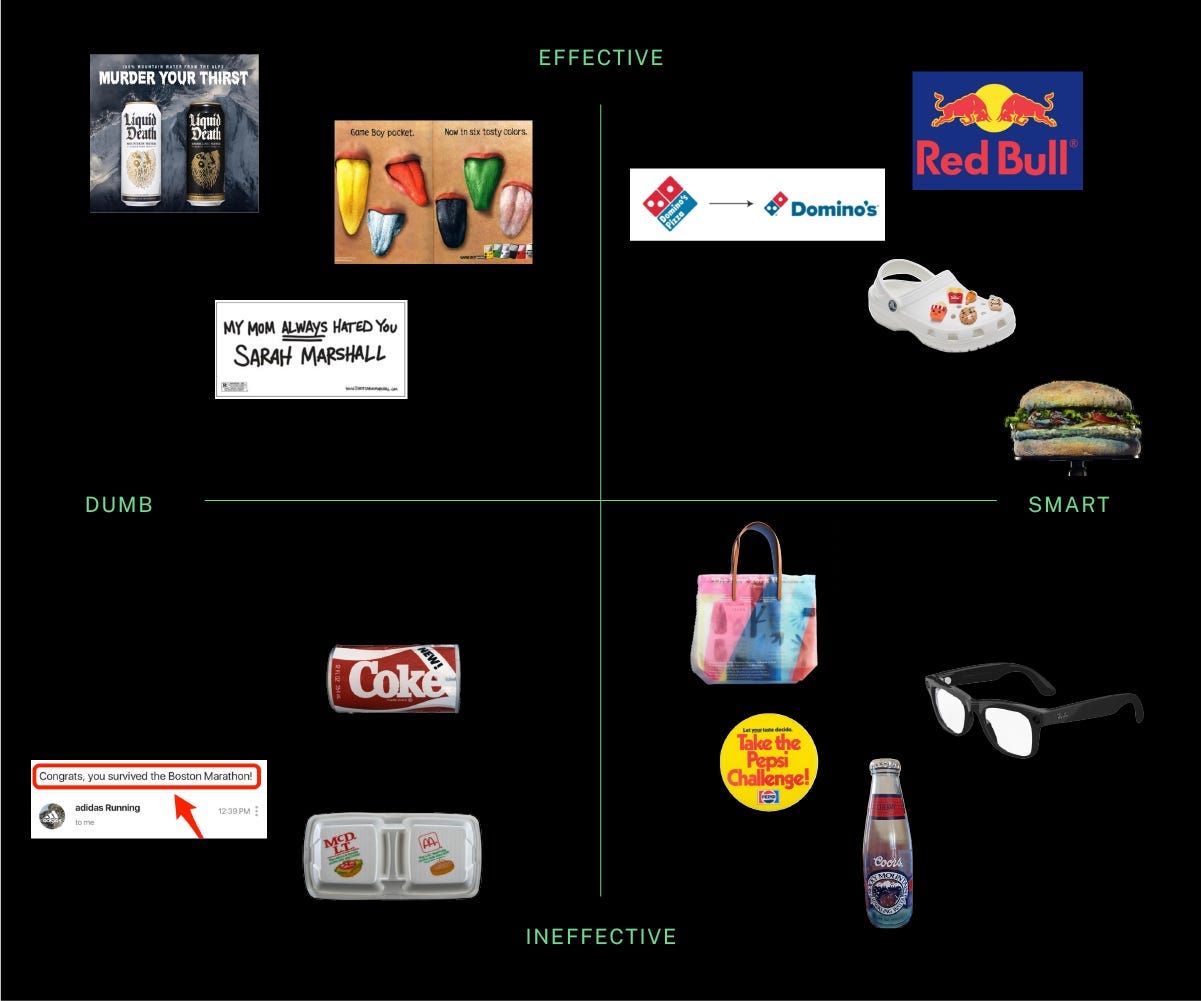

The Matrix of Gimmick Effectiveness

So gimmicks writ large represent something essential about humanity, and all gimmicks are not created equal. That’s why we’ve created our own system for assessing the effectiveness of gimmicks across time and industries, along with a handful of deep dives into some notable case studies.

Aspiring to the level of the best gimmicks, we’re making this as simple as possible, with our X-axis accounting for the cleverness of the gimmick and our Y-axis speaking to its effectiveness. Behold:

Case Study: The McDLT

Dumb and Ineffective

The 80s were…really something. Back then, the powers-that-were at McDonald’s realized customers could enjoy a fresher-tasting burger if the hot component (burger patty) was kept separate from the cold components (lettuce and tomato) until the consumer decided they were ready to eat it. Which…sure?

The McDLT was shelved for good in 1990 amid environmental concerns, as styrofoam was the only material capable of simultaneously preserving both temperatures, and the packaging necessitated a lot of it. But the deeper problem here was the flimsy assumption on McDonald’s part that people go there for the freshest burger in town, which is not really their calling card.

However, every storm has its rainbow, and the McDLT did give us Jason Alexander's finest hour this side of George Costanza.

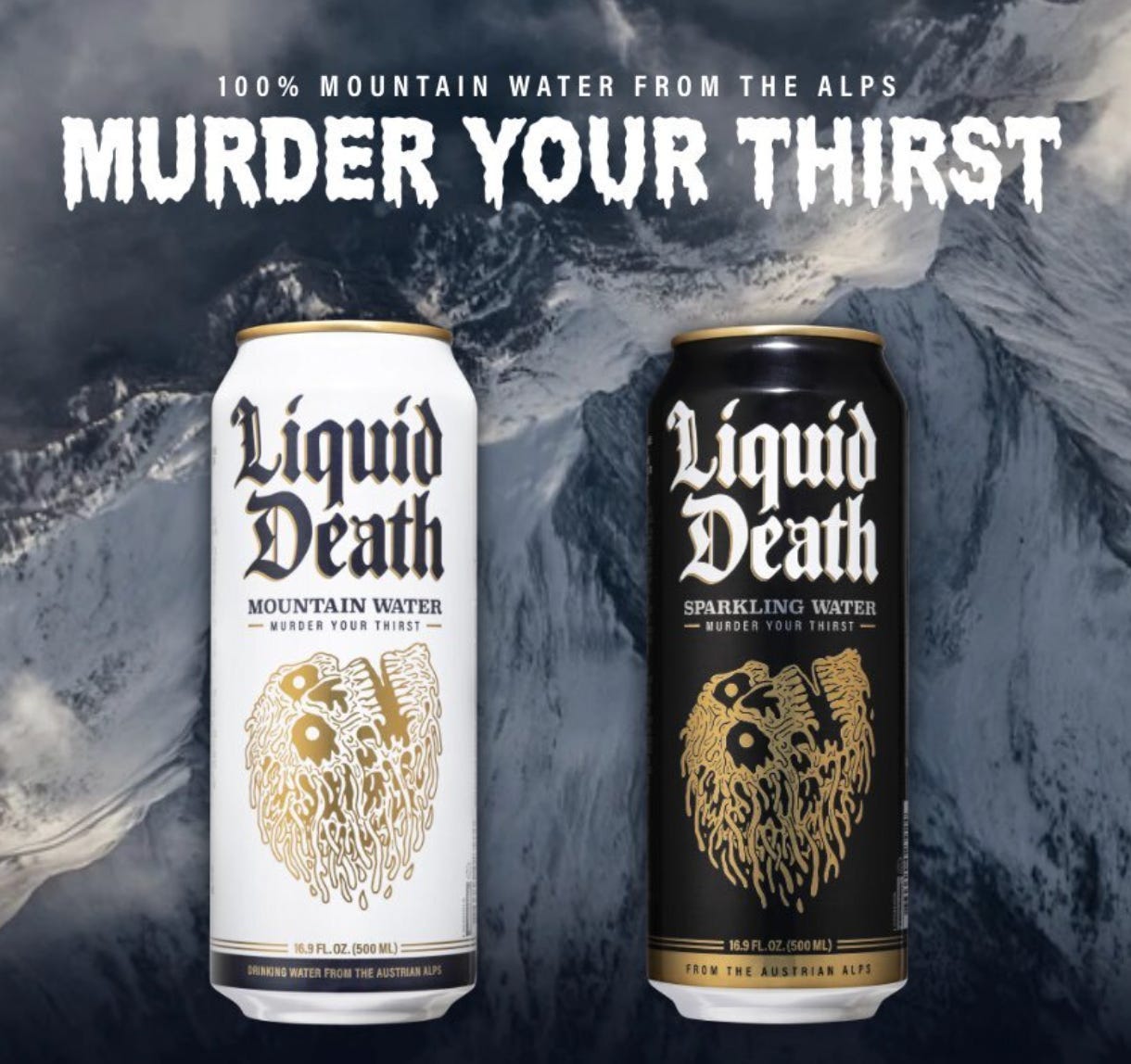

Case Study: Liquid Death

Dumb and Effective

Liquid Death pretty much falls into its own category of “so dumb it’s smart,” which may be the most advantageous place to be as a brand.

Founded in 2018 by graphic designer and marketing veteran Mike Cessario, Liquid Death owes its look and vibe to Cessario having attended the Vans Warped Tour in 2009, which at the time was sponsored by Monster Energy, and where Cessario discovered that despite the drink’s supposed ubiquity among performers, many were actually dumping out the sugary stuff and replacing it with water.

That discovery led to the realization that canned water would stand out in a crowded water bottle market, and present an opportunity for an unprecedented style of messaging. “Murder your Thirst,” goes the brand tagline, but according to Cessario (who himself acknowledges the dumbness at play), the internal company motto is “Death to plastic,” bringing a hardcore style of communication to a mission that is historically pretty toothless.

This gimmick works on all levels. It brings a heavy metal ethos to healthy life choices and environmentalism. There is scientific evidence that aluminum cans keep drinks colder, providing a functional UVP. And the cans are not only a superior vessel, but a conversation starter. Every can of Liquid Death consumed presents an opportunity to initiate the uninitiated.

Case Study: The Pepsi Challenge

Smart and Ineffective

Pepsi has always been the little brother soda, or maybe the cousin-you-only-see-at-weddings soda, compared to you-know-who. In 1975, after nearly a century of being an also-ran, they decided they’d had enough, and launched what would become a nationwide push to convert people from C*ke to Pepsi.

Beginning in Dallas area malls, the challenge was as simple as it sounded. Blindfold people, give them a taste of each soda, ask them which they prefer. And if their footage is to be believed, the results were good. People preferred Pepsi over Coke by a considerable margin— so considerable that Coke panicked, launching negative PR attacks and eventually introducing New Coke.

The problem with the Pepsi Challenge (other than evidence that the challenge failed to account for people’s preference over an entire serving of soda, rather than a single sip), was that despite building a crazy amount of momentum, Pepsi did not fully commit to their gimmick. They got scores of people to admit on camera to preferring their product over their main rival, which is an amazing start, but a start is all it is. There were no follow-up efforts to change consumer habits–no coupons or other rewards handed to the people who chose Pepsi over Coke. The Pepsi Challenge, for all potential, wound up just being a moment in time.

(And from the aforementioned Netflix doc Pepsi, Where's My Jet?, it would appear that Pepsi’s lack of follow-through is a chronic issue.)

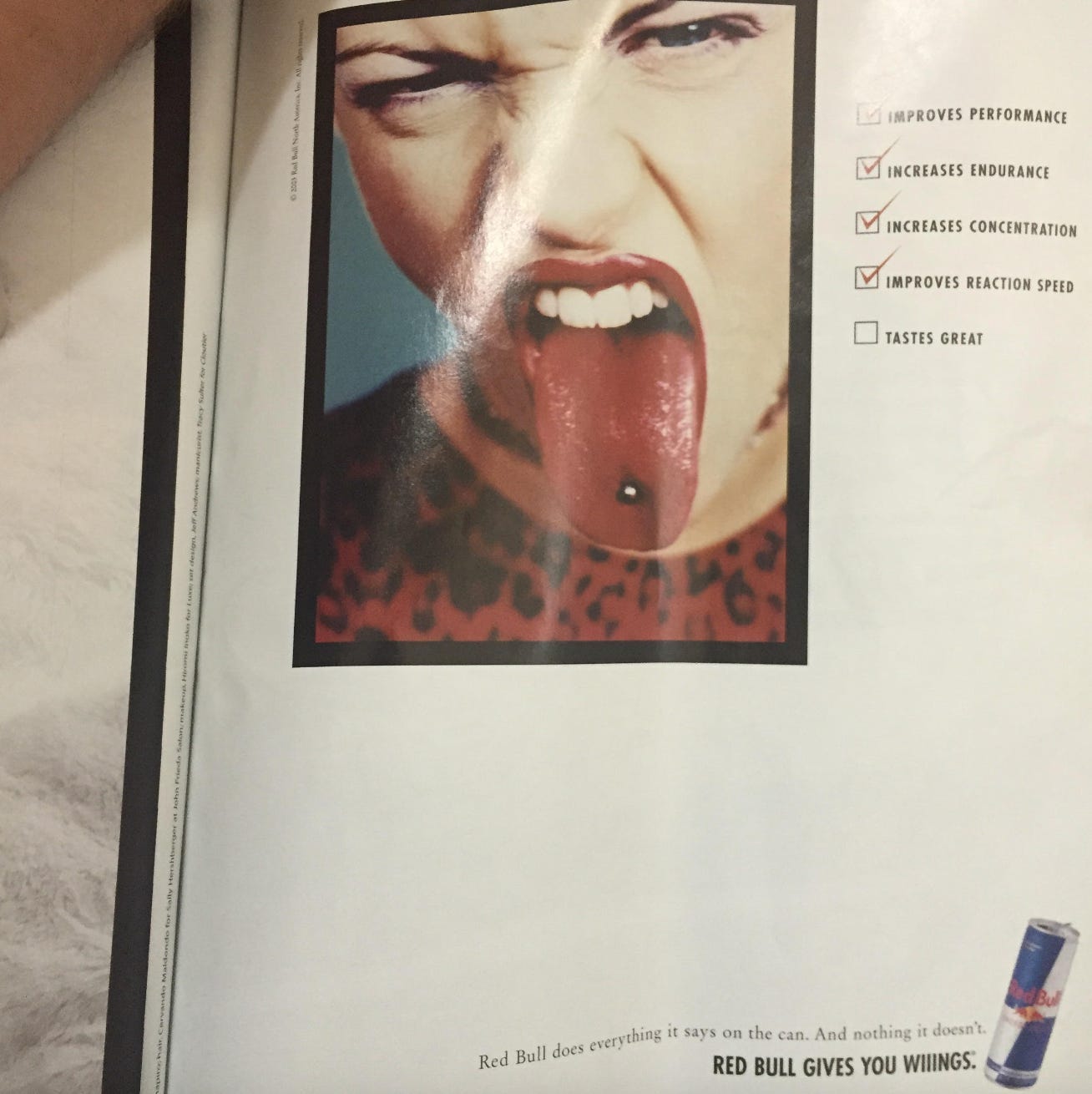

Case Study: Red Bull

Smart and Effective

“Red Bull gives you…” Well, almost everything at this point.

As of this writing, Red Bull is the owner of seven soccer teams, two Formula One teams, two ice hockey teams, an eSports team, a fashion brand, and a record label. That’s to say nothing of the professional and amateur stunt events they stage—where normal citizens attempt, per the brand tagline, to give themselves wiiings—or the space jump by Felix Baumgartner they orchestrated in 2012, the height of which was actually bested in 2014 by former Google exec Alan Eustace, but honestly nobody really cared about that because it didn’t look as cool.

Oh, and they still make an energy drink too.

All this to say: Red Bull is the prime example of total gimmick transcendence. Launched in 1987 by Austrian Dietrich Mateschitz, the drink itself was modeled on the functional energy drinks of East Asia, and positioned not as a beverage to be savored, but rather as fuel for your ambition. The 1992 introduction of the tagline “Red Bull gives you wings” (later amended cleverly to “wiiings”) perfectly encapsulated that ethos, and everything that has sprouted from the Red Bull brand since has everything to do with that spirit, and not much to do with the specificity of the drink itself.

Sure, maybe the Red Bull athletes drink it, but you’ll never catch any of them (or anyone, for that matter) professing their love for its flavor, and that’s by design. They even leaned into its reputation for tasting bad in a 2006 print campaign:

The gimmick here is that it’s not what’s in the can that matters, as with all other beverages — what matters is whatever is inside you, and the can is just the key to unlock whatever that is.

That will fly forever.

Moodboard

Reading List

Convinced it’s time to embrace the Gimmick? Here’s some places to start learning more:

Theory of the Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form — Cultural theorist Sianne Ngai makes the case that the gimmick is a particularly capitalist category due to its mismatch of labor and value.

The Verificationist — Donald Antrim’s 2000 novel takes place entirely during a pancake dinner held by a group of psychologists. Good gimmick? See for yourself.

Max Pain — Nemesis’s 2022 memo coins the term “Clown Town” for the era when meaning and value became separated; causing absurdism, big swings, and, one could say, gimmicks, to come back into style.

My Journey North — Ever wanted to hear Hodor’s Game of Thrones journey told in his own word(s)? Then this is the gimmick for you.

Hey Whipple, Squeeze This! - This “Classic Guide to Creating Great Advertising” is chock-full of gimmicks that worked great including “how to go 180˚ against common sense for ideas that have the potential of becoming viral.”