CODEX 001 : In A Name

Welcome to the first edition of Kingsland's CODEX: a newsletter about how to think about thinking about marketing, advertising, and communication.

{In A Name}

“What’s in a name?” It was Juliet herself who first posed this question in Act II of the debut performance of Romeo and Juliet at The Theatre in London in 1597.

That’s right: THE Theatre, which would soon be disassembled board-by-board and moved across the river Thames, where it was rebuilt and given its more iconic moniker: The Globe.

Shakespeare and Co. believed in the power of naming — they chose “The Globe” after the mythological image of mighty Hercules carrying the spherical world upon his shoulders, just as their actors carried the theater’s old timbers across the river. They clearly cared about branding too, adorning their new playhouse with the flag of Hercules emblazoned with the Latin motto totus mundus agit histrionem, or “all the world’s a stage.” They obviously did not care about being pretentious.

Four centuries later, little has changed: Theater nerds still carry a penchant for drama (we love you, we’re nerds too), and names still help us convey meaning — and value — with only a few letters. Names are also the theme of the first-ever edition of The Kingsland Codex, our brand-new newsletter… which we may rename.

Connections:

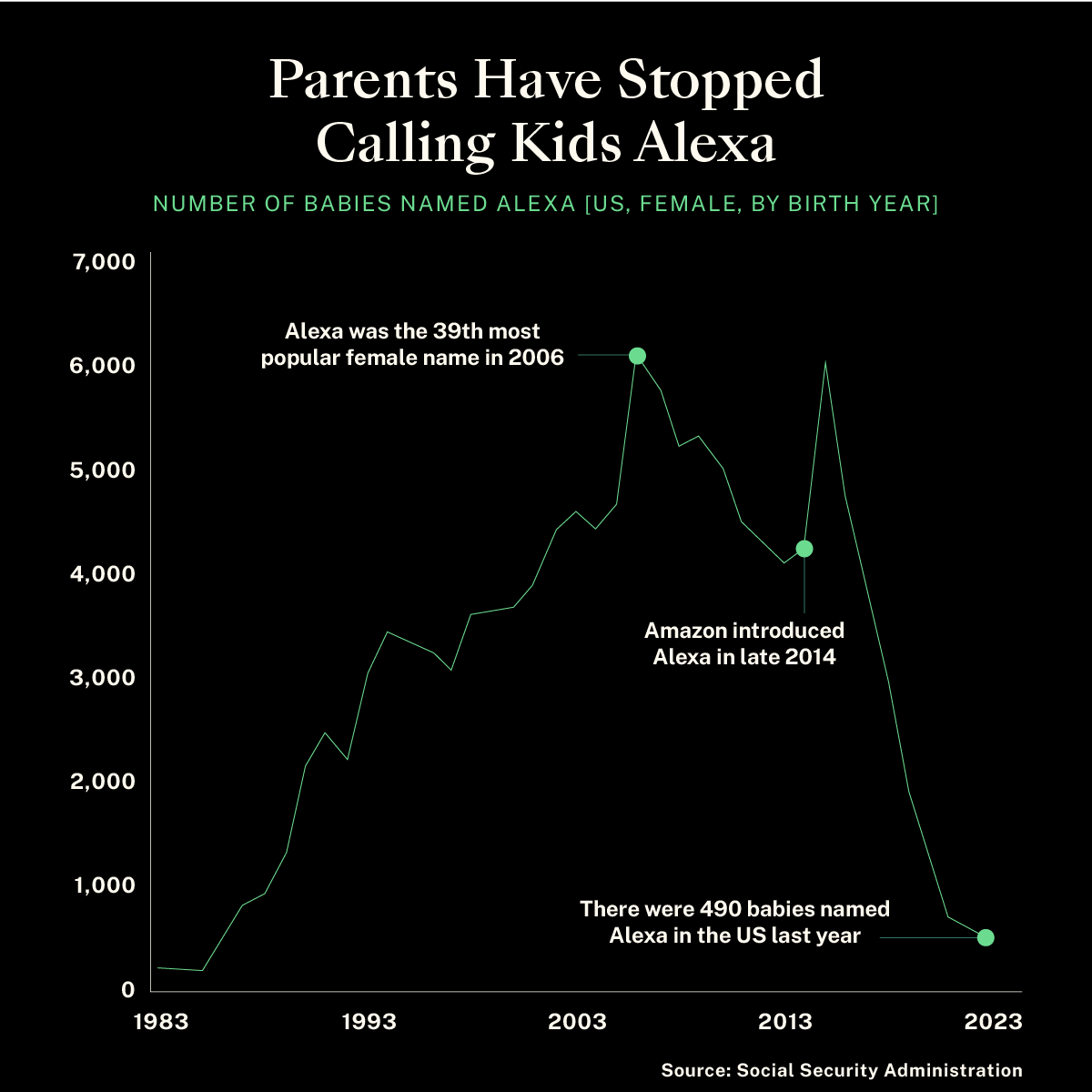

🤖 Alexa • Hillary • Katrina → All baby names that trended downward due to their famous namesakes.

🏈 Charles Dickens • The NFL • Pharmaceuticals → All contain wonderful naming inspiration, even when they’re being satirized.

👩 Ancient Egypt • A Former Coworker • The AI in Halo → The inspirations for the names of three leading voice assistants. (Still, Google’s voice assistant — just called “Google” — is the most popular.)

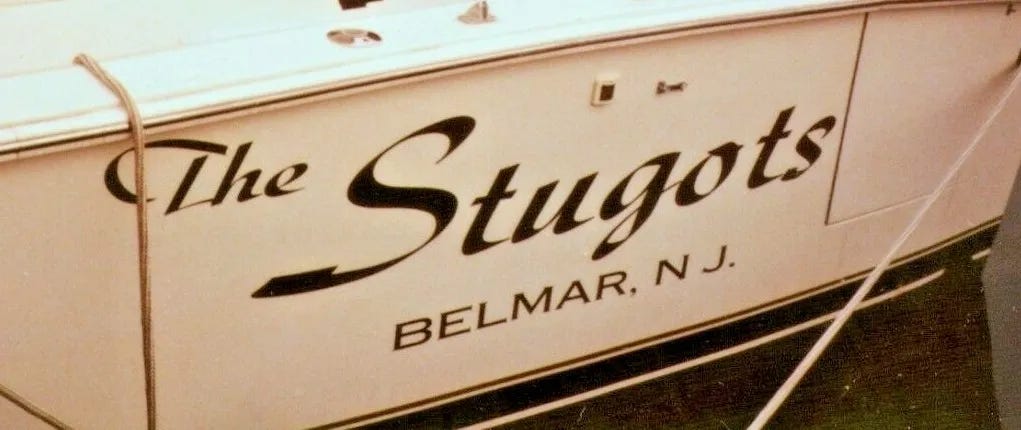

🐎 Racehorses • Boats • Outer Space → Serious things. Silly naming conventions.

🍎 Red Apple • Soylent Green • Blue Magic → All colorful brand names from the world of cinema. Some rooted in reality, others served to inspire it.

💅 Plaey • Astronova • Jaywalk → Three products we’ve named at Kingsland.

The Commonplace:

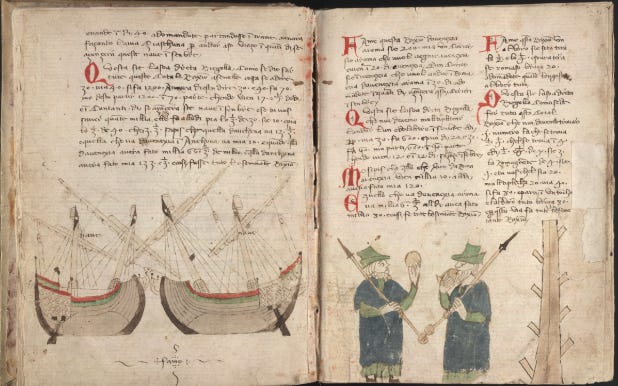

A medieval commonplace book, or “zibaldone,” circa 1350.

What is a Commonplace?

A commonplace book is a hodgepodge of secret knowledge, new ideas, old quotations, and odd observations compiled for future reference and reflection.

It’s an age-old scholarly tradition: Seneca and Cicero maintained notes as loci communes, or "commonplaces.” Fourteenth-century Italians kept what they called zibaldone, which literally translates to "a dish made up of various and mixed ingredients.”

And it’s a group endeavor: As medieval Europeans learned to read and write, commonplaces could be found at inns, universities, houses of worship, and more.

Why Do We Care?

Our brains hold no hierarchy. We are an ever-expanding web of firing neurons that constantly reshuffle and reprioritize our memories to accommodate new knowledge. The Romantics called the mind “magic” while scientists call this “neuroplasticity.” We call it a commonplace.

At Kingsland, trivia is anything but trivial. Those stray scraps of arcanum often coalesce in unexpected ways. This newsletter will always feature a compendium of loosely-related links, facts, and stories that may do nothing more than inform. But by sharing them and inviting you into our commonplace, we increase the likelihood that they may brush against each other and spark something new — for us and for you.

The Commonplace: Naming Names

Death & Taxes & Death Taxes: Two decades ago, notorious Republican strategist Frank Lutz advocated for the use of vocabulary crafted to produce a specific desired political effect; including the term death tax instead of estate tax, and climate change instead of global warming. It worked, and kicked off an era of Congress naming bills after almost anything other than what they actually are.

The Boys Aren’t Back In Town: After 114 years, the Boy Scouts of America is rebranding to Scouting America. Will it be enough to save the troubled organization’s image? Will they ever start selling cookies? Only time will tell.

Visit Truth Or Consequences!: New Mexico, that is. A town-turned-publicity stunt that renamed itself after a popular 1950s radio show. This happens more often than you’d think.

Drink Me By Your Name: Coke’s 2014 “Share A Coke” campaign, replacing the soda’s logo with customers’ names, increased sales for the first time in a decade.

Yes We Lexi-Can: The naming experts behind brands like “Blackberry,” “inDesign,” “Lucid,” and “Impossible” are bullish on AI products, but humans are still naming them… for now.

Don’t Be Evil: After rolling out generative AI on Google Search—a move web publishers feared would be “catastrophic”— Google has renamed its “AI Answers” feature back to “AI Overview.”

Bob & Carol & Ted & Ignatius: According to author Tony Tulathimutte, the two dominant camps of character names in contemporary novels are the realistic name and the Pynchonesque “absurdonym.”

Hopelandic Springs Eternal: Sigur Ros once made up an entire language for one of their albums.

Picture This: Photographer Alec Soth shows off his library of rare photobooks while musing over how naming a photograph can provide context to an image while simultaneously deepening its meaning.

“CEMETERY, FOUNTAIN CITY” by Alec Soth.

Column: By Any Other Name

-Douglas Brundage, Founder & Head of Strategy @ Kingsland

Successful brands know that a good name can change everything. So if naming is so imperative to branding, why is the act of naming so misunderstood?

For both companies and people, a name is a brand, and vice-versa. It’s why we wear clothing from Ralph Lauren and not Ralph Lifshitz. It’s why Elton John and Bruno Mars sell out arenas while Reginald Kenneth Dwight and Peter Gene Hernandez stay in the green room. It’s why names like John Wayne, Meg Ryan, and Jamie Foxx are synonymous with Hollywood — because Marion Robert Morrison, Margaret Mary Emily Anne Hyra, and Eric Marlon Bishop don’t look as good lit up on a marquee. No one is flocking to see Mark Sinclair pull off increasingly implausible automotive stunts — but we will when he’s named Vin Diesel.

Of course, sometimes names change due to a lack of cultural acceptance or perceived pronunciation problems — something most immigrants in the U.S. (and beyond) understand intimately. Although today we have superstars like Chiwetel Ejiofor, Saoirse Ronan, and Giannis Antetokounmpo, it’s still exceedingly rare for brands to launch with names that won’t roll off the tongue of English-speaking consumers.

Names that are too complex or unfamiliar can be a negative, but no one wants a bland brand, so the best names split the difference — easier said than done. The key is approaching naming from both a scientific and an artistic perspective.

Naming is a Scientific Process

More than ever, brands suffer from intense scrutiny. According to Nielsen, the average consumer spends about 6-13 seconds purchasing a brand in-store or online, with the majority making their decision in under 10 seconds. With such a tiny window to trigger a purchase, signifiers like color, packaging, claims, and indeed naming matter tremendously. For this reason, brand names (especially for newer companies without huge marketing budgets) must be Simple, Easy to Pronounce, and Memorable.

Simplicity is directly tied to memorability. Our brains have pre-set structures for how to remember things, and neuroscientists have proven that long words are typically recalled more poorly than short words. This is due to the greater demand that longer words place on cognitive structures called phonological encoding, rehearsal, and production. The ideal range for naming consumer brands: one to three syllables, max.

Easy pronunciation is key, but so is translation. An Italian coffee brand with the lovely name Paska is still sold in Finland, despite the fact that it directly translates to “shit.” Colgate once launched a toothpaste in France called Cue, without realizing that it was also the name of a much-loved erotic magazine. Mazda launched the Laputa minivan in Spain in 1991. Unfortunately, the name directly translates to “the prostitute.” Even more unfortunately, Mazda’s sales copy crowed that “Laputa has a lightweight, impact-absorbing body.” Can’t make this stuff up.

This all means that launching a brand internationally requires a bit more leg work. Some letters in the Latin alphabet sound consistent across languages: the letters B, K, L, M, N, P and R, for example, tend to be pronounced the same way. But letters like C and G can have different sounds even within the same language — and letters like J and X can be pronounced very differently even within the closely-linked Romance languages.

Beyond translation, naming must consider both phonology and orthography: how a word SOUNDS when spoken, and how it LOOKS written down. The general rule is that vowels are our friends and consonants are not, especially when they are “clustered” (in words like “Sixths,” “Glimpsed,” or “Angsts”). This is because vowels are not only more visually appealing, but also more common in the vast majority of languages spoken worldwide.

Quantitatively, brands should not launch products with difficult to pronounce names, especially in the U.S. But qualitatively, there are some contradictions. For example, Americans are culturally obsessed with European (and especially French) brands as a signifier of quality and luxury. So while U.S. consumers may mispronounce it, they still buy Moët to celebrate and Givenchy to show off. In fact, butchering a brand name can sometimes encourage conversation and recall — in the UK, for example, they pronounce “Nike” like “Mike” instead of “Nye-Kee.” Although these are well-established brands, new companies can lean into a bit of transatlantic mistranslation for mystique — just look at Levain, Häagen-Dazs (founded by two Jews in the Bronx), or Aimé Leon Dore.

Remember memorability? Sure, we can use the science to engineer a short name with the right amount of consonants and make sure it passes our phonological and orthographic tests — but is that enough to stand out and be remembered? This is where science takes a backseat to its softer cousin: Art.

Naming is an Artistic Process

We’ve established the rules of naming: now it’s time to break them. Scientific processes are standardized, but the Emotional ones are not, and naming is intensely personal. A brand or product name should be tailored to the specific company, target customer, and industry. For startups, it should also reflect the founder — we tell founders that the name they pick should make them smile when they see it.

We use both the scientific and artistic approach to naming because word choices matter, now more than ever. Naming is an imperative building block for how your brand will be perceived in the market, and the right name has brand-building advantages: just look at Liquid Death, one of the fastest-growing beverage brands in history. That name breaks many rules, but it also follows several (easy to pronounce, short, descriptive, memorable). It’s simply water in a can, but the unconventional moniker has been a springboard for an entire brand world that is just as edgy and defiant as its name.

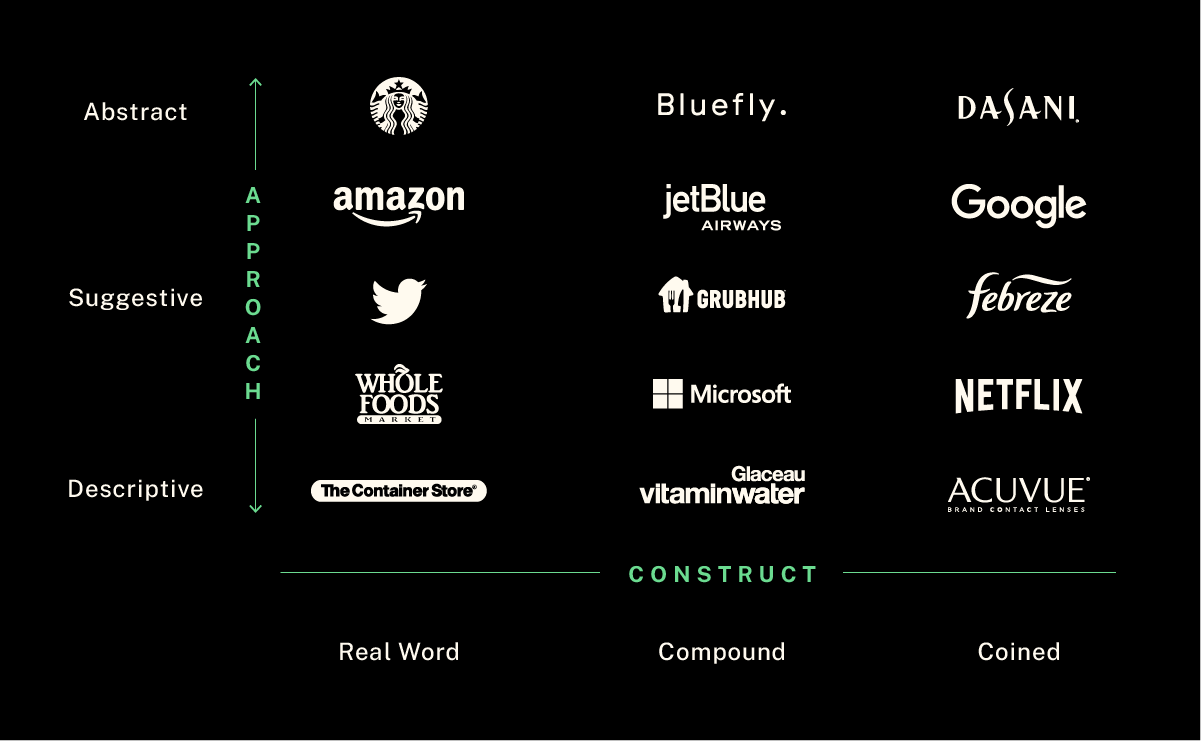

Even when breaking the rules, it is still helpful to use a tool like a Naming Taxonomy, which gives a name to the types of names you can name something — stay with us here.

Descriptive names (Vitamin Water, The Container Store) get the job done, but can lose memorability without standout marketing or a rich brand world. Suggestive names (Uber, Nike) can be soaring and inspiring, but if they don’t somehow connect to the product they can cause confusion. The same applies doubly for Abstract names (Apple, Virgin), which may have zero relation to their product, but are more likely to evoke and provoke emotion.

This taxonomy is more important than it seems, because for many consumers, brands exist entirely as a name and nothing more. Choosing the right type of name can set a foundation for messaging and marketing, and set a tone for how a brand world develops and evolves over time. There is an element of projection and gut-feeling to naming — hence the artistry.

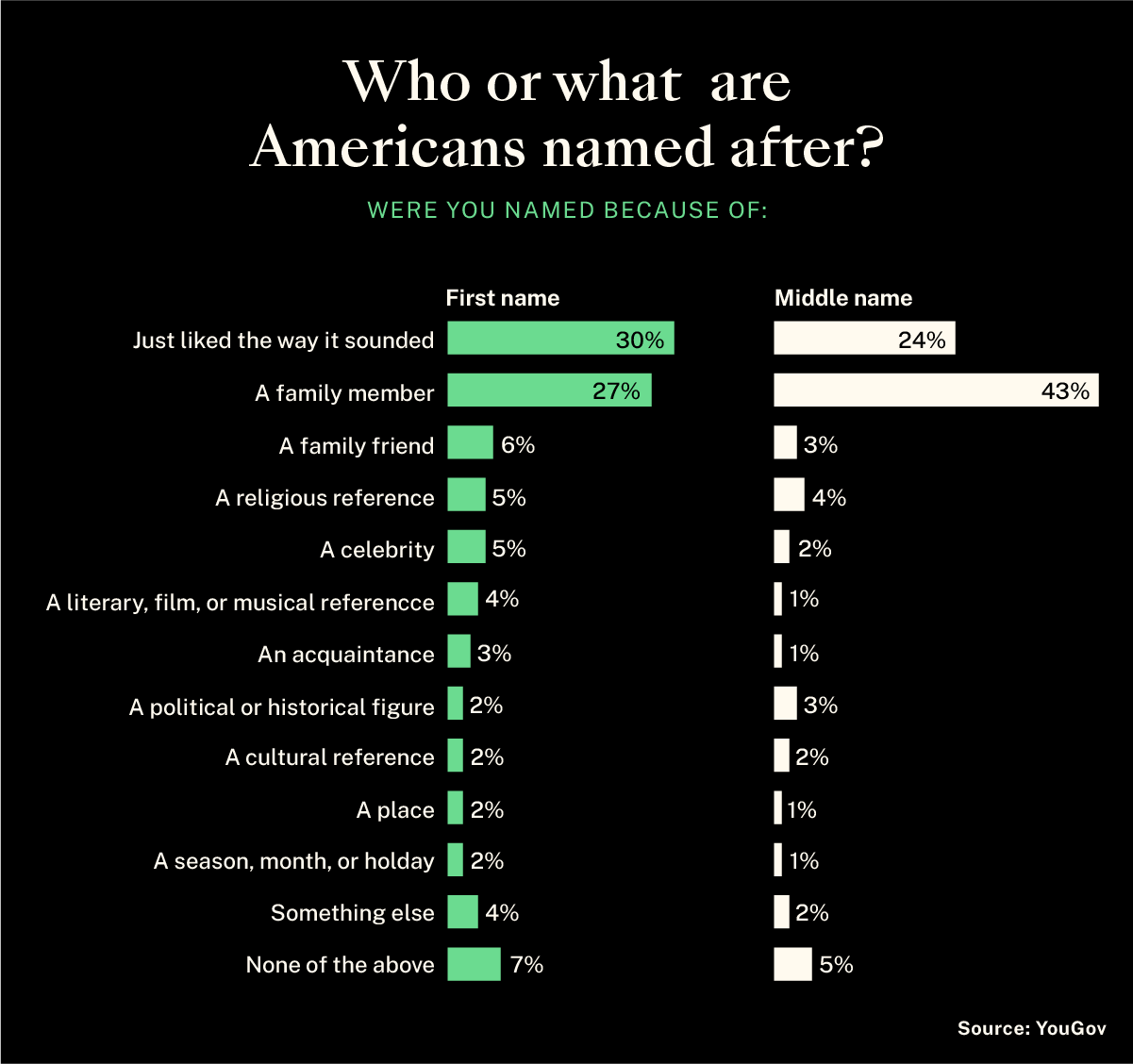

Finally, remember naming is not immune to trends. Take trends in baby names over the last 100 years as an example. The goal is to name your brand (and probably your child) something that will feel timeless, rather than explicitly of-the-moment, so you don’t end up with a brand named after a forgotten meme or a generation of girls named “Khaleesi.”

What Should a Name Do?

Juliet was correct in asserting that “a rose, by any other name, would smell as sweet.” It just wouldn’t technically be a “rose” anymore.

What Juliet overlooked was semiotics. One of the defining human traits is our ability to use language. Communication led to cooperation, and our ability to carry out complex tasks as a unit gave us an intense evolutionary advantage back when we were hunting Wooly Mammoths and evading Saber-toothed Tigers. When we name something, it becomes something else — a word itself is imbued with symbology beyond literal description. When you say “puppy,” most people smile. If you say “juvenile canid,” they probably won’t.

A rose is more than a flower: it is a symbol for love, among other things. In this way, meaning transcends the name itself — call it “Nigh-k” or “Nye-kee” or “Ni-Kee-Aye,” Nike still stands for performance.

Ultimately, a name is what you make of it. A strong name is a head start, while a weak one hinders your progress, regardless of the quality of your brand or product. But never disregard the strategic, scientific, emotional, and cultural implications of your decision: no matter how beautiful and fragrant they may be, no one wants a bouquet of stench blossoms for Valentine’s Day.

Moodboard

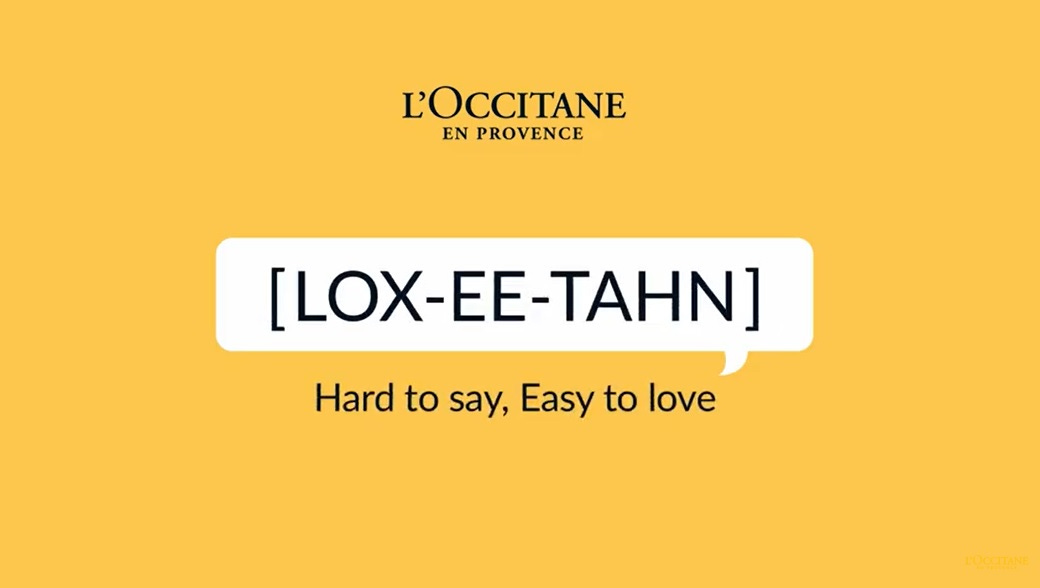

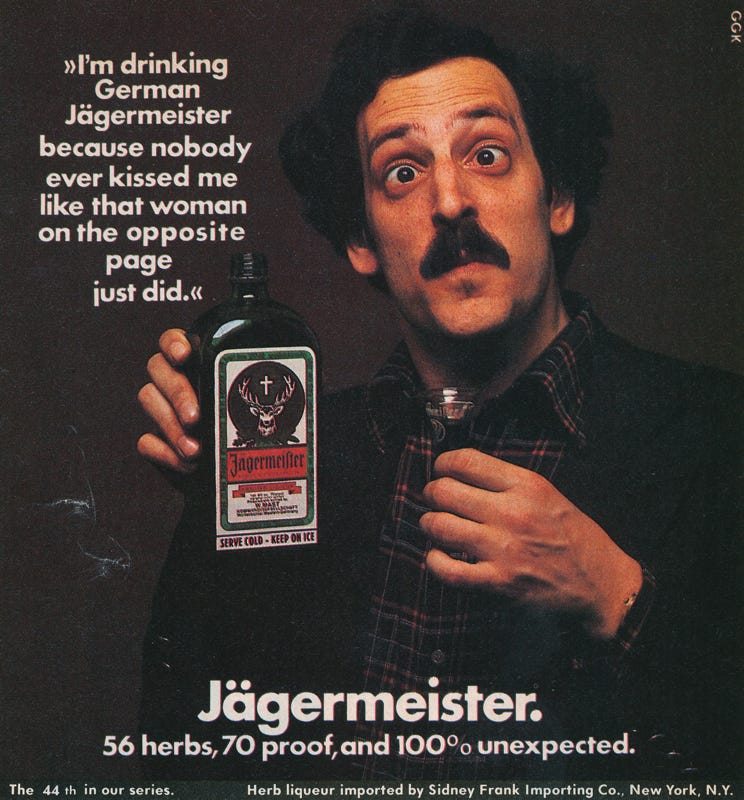

Most ads that try to educate the customer on how to pronounce the brand name correctly look like this:

A good ad that tries to educate the customer on how to pronounce the brand name correctly looks like this:

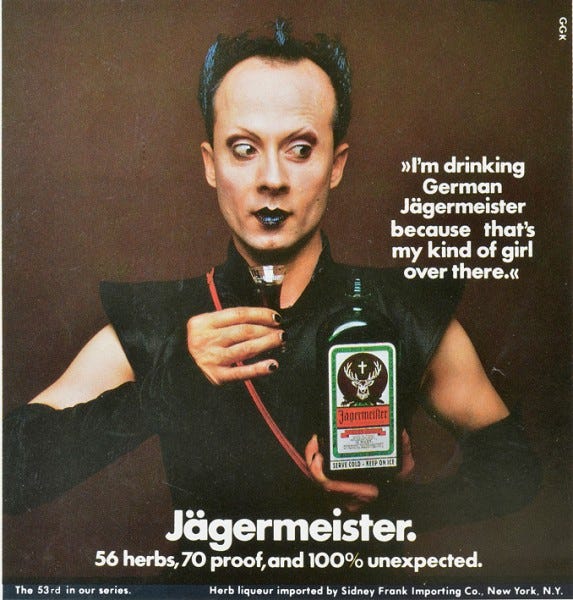

Difference or “distinctivity” in the marketplace is all the rage today. Here’s a campaign from a brand that would be almost impossible to pronounce correctly in the U.S. without cultural relevance, built from a distinctive brand positioning anchored by “New Wave Vaudeville” star Klaus Nomi, circa 1980. 56 portraits to embody the 56 herbs used in distilling Jägermeister:

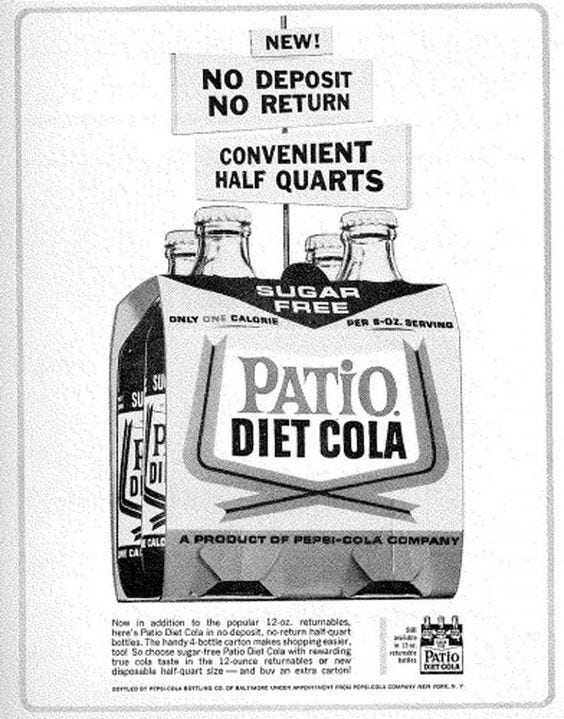

Diet Pepsi used to be called PATIO. It even was featured on “Mad Men.” For anyone who works at PepsiCo, it might be a good time to bring back this beautifully funky wordmark.

The best names tie into a larger product narrative. Take Crazy Eddie, whose prices were “INSANE!” Founded in 1971 in Brooklyn, the consumer electronics chain was so successful it eventually traded on the NASDAQ (under the stock symbol CRZY, obviously). The brand’s commercials were so nuts and memorable that HBO's “Not Necessarily the News” created a parody television commercial featuring a caricature of Oliver North (of Iran–Contra fame), known as "Crazy Ollie," selling used weapons at bargain prices. The brand has had cameos in “X-Men,” “Russian Doll,” and “The Accountant,” among other film and television productions. Unsurprisingly, but true to their name, the company was involved in illegal practices almost from Day 1 —crazy Eddie Antar himself landed on U.S. Marshal’s “Most Wanted” list by 1990. Pretty crazy.

Reading List:

Having a hard time coming up with a name for a product, pet, or person? Here are some great places to start thinking:

Name Generators: Sure, AI can help you come up with names, but so can these more interesting sources of inspiration:

Desert Storm, Rolling Thunder, Barbarossa - How the US Military Names Their Operations.

Childish Gambino, Gentlemen Desperado, Bittah Wizard: Enter the Wu Tang Name Generator.

Gandalf, Digory Kirke, Baron Greyfallow: Consider the Fantasy Name Generator.

Don’t Call it That: A Naming Workbook - We generally avoid “How-Tos,” but this is one of the best ones we’ve found, right from the source of naming firm A Hundred Monkeys.

Experiencing Architecture by Steen Eiler Rasmussen - Ever wonder about the theatrics of architecture and its impression on the collective psyche? Us too. Look no further.

House of Leaves - Think outside the box, or inside many small boxes, or around the margins of the page, with Mark Z. Danielewski’s debut novel that makes Infinite Jest look lazy in terms of inventive formatting.

The Social Security Administration's Baby Name Database - This goes all the way back to 1879, and serves as a nice reminder that everything happens in cycles. Don’t sweat originality too too much.

Jabberwocky by Lewis Carroll - Can’t find the words you’re looking for? Make them up — you slithy toves.